Charlie Cobb received a less-than-warm welcome when he arrived in Ruleville, Mississippi, as a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) volunteer in the summer of 1962.

A white man stopped his car next to him on one of the town’s dirt roads and showed the young Howard University student his pistol.

“He said, ‘I know y’all ain’t from here, and I know you’re here to cause trouble. I’m here to tell you to get out of town,’” Cobb said. “This guy turns out to be the mayor.”

Such public displays of intimidation were common in the Jim Crow-era Deep South. But SNCC organizers, college students who worked in segregated communities throughout the southern states in the 1960s, found ways to empower African-Americans to register to vote. Their methods, including sit-ins and freedom rides, were in stark contrast to the violent racism they encountered in places such as the Mississippi Delta, where Cobb spent four years.

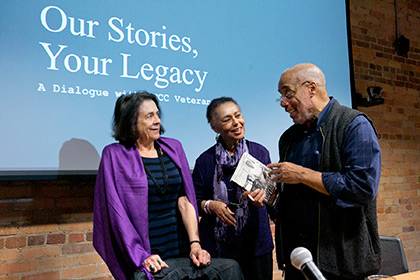

Cobb, now a veteran foreign affairs reporter and author, joined fellow SNCC organizers Maria Varela and Judy Richardson in the Franklin Humanities Institute (FHI) Garage on Wednesday night to share accounts of their time in the organization. The panel discussion, “Our Stories, Your Legacy: A Dialogue with SNCC Veterans,” was sponsored by the Forum for Scholars and Publics, FHI, the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS), Department of History, the Duke Human Rights Center and the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture (JHFRC).

The Wednesday event was part of Duke's continuing partnership with the SNCC Legacy Project to document the Civil Rights era.

The event also served as an introduction of the SNCC Digital Gateway, a forthcoming “documentary website” containing written, visual and oral historical materials. The Gateway is a collaboration between the CDS and Duke University Libraries and will become available to the public in December 2016. John Gartrell, director of the JHFRC who also moderated Wednesday’s panel, said documenting the experiences of activists such as Cobb, Varela and Richardson was critical to the survival of present-day social justice movements.

“We are hoping the gateway will be a dynamic resource that people of all ages will be able to use,” Gartrell said. “The great thing about it is that we are using the actual voices of the people who did all this groundbreaking work [in the 1960s] to put it together.”

Following Gartrell’s introduction of the Digital Gateway, the discussion focused on the first-hand accounts of SNCC veterans Richardson, Varela and Cobb.

“Organizing is about the invitation,” said Varela, a lifelong community organizer and photographer. “It’s not about mass meetings and great leaders and beautiful posters and wonderful speeches. It’s about someone saying, ‘I watched you [do] something and I really think we could use you in our movement.’ That invitation is what builds a movement.”

All three activists noted that the challenges of institutionalized racism did not disappear when SNCC and other grassroots Civil Rights-era organizations shuttered their operations in the 1970s. Cobb cited the continued work of the Black Lives Matter and other present-day social justice movements and offered advice to young community organizers.

“You have to be sensitive to the fact that you are working with people to help them find their own strength, their own power,” Cobb said. “As an outsider, you have to learn how to listen to [the locals].”

Drawing from her experiences on the production team of PBS’s acclaimed Civil Rights documentary “Eyes on the Prize” in the 1970s, Richardson also spoke to historians of social justice movements.

“The danger of only seeing Dr. King in accounts [of the Civil Rights era] is that you then start to think, ‘if only Dr. King was here,’” Richardson said. “[In “Eyes on the Prize”], we really tried to show the movement outside of Dr. King.

“Unless you see people who look just like you building and sustaining a movement, you won’t think you can do it, too. I want to remind today’s young people that people just like them changed the world as we know it.”

For more information about upcoming CDS events, click here.